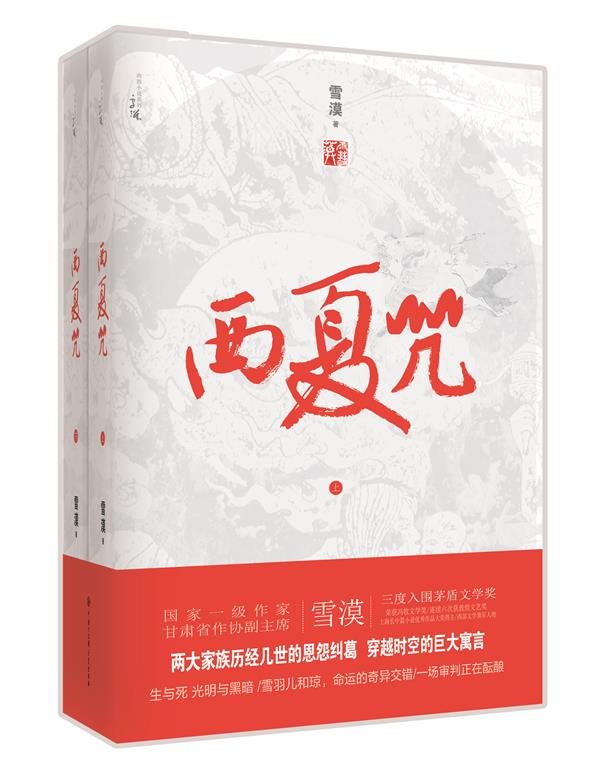

Existence,

Illusion, and Time in Xue Mo's Curses of the Kingdom of Xixia.

By Andrea Lingenfelter, PhD

Thematically

rooted in the Tibetan Esoteric Buddhism practiced by its renowned author Xue

Mo, the novel Curses of the Kingdom ofXixia takes readers on an extended

journey through time. Events depicted in the novel take place in a handful of

key locations near the ancient town of Liangzhou (present day Wuwei, Gansu

province). Crafting a story that spans roughly a thousand years but remains in

one place, Xue Mo creates on the page a densely layered world of simultaneity

and impermanence. This essay will discuss the structure, style, characters, and

the broad outlines of the many tales contained in Curses of the Kingdom ofXixia,

connecting all of this to some of the novel’s important themes, including the

Buddhist concept of impermanence and a code of ethics informed by Buddhism.

Although this article will leave a more extensive and learned analysis of the

novel’s Buddhist concepts to specialists, I will nonetheless call attention to

concepts that are essential to our understanding of the text.

Structure:

The

Frame:

The

novel’s structure is modeled on traditional Chinese novels. As is common in

traditional works of fiction like Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE) chuanqi (literary

short fiction) as well as the earlier zhiguai tradition of urban legends, the

author/narrator often constructs a frame story introducing the provenance of

the tale we are about to read in terms of real-world events. This grounding in

verisimilitude is an important feature of early traditional fiction. In a

similar fashion, in the opening pages of Curses of the Kingdom of Xixia, the

narrator identifies himself as the author Xue Mo and Treats readers to detailed

account of the genesis of the novel. In the novel’s opening pages, he tells of

the discovery of a cache of eight ancient manuscripts in a grotto located in

territory that was once part of the ancient kingdom of Xixia (1038 – 1227 CE).

The population of Xixia itself was obliterated by the armies of Genghis Khan,

erasing the kingdom from the map; but this collection of manuscripts, written

in different hands and on different paper stock —mostly in Chinese but with

some phrases written in the lost language of Xixia — surfaces in the late 20th

century.

“Everything

started with a rock fall,” the narrator

tells us, making it sound like a chance event; but nothing that happens in this

novel is coincidental.

Xue

Mo employs a strategy common in Tang chuanqi, whereby the narrators would

describe, often in some detail, how they first heard the story they are about

to relate, along with who they heard it from. He names the person he learned

about the discovery from, leavening the account with earthy humor, while also

suggesting the cosmic forces at work in the unearthing of the lost texts:

According

to an old man surnamed Qiao, rocks fell several times in that cave. Once when

the grotto was being repaired, a fella said, “Why repair such crap?” A huge

rock tumbled down past his head and took his hat with it.

The

same thing happened when we performed our ritual offering. Just as we were

chanting the Offering Mantra to the point of forgetting ourselves, a rock

plummeted and smashed a mud pagoda. There were many such pagodas in the cave,

which were originally used to house the relics of venerable monks. However,

this pagoda did not contain any relics. It housed a pile of manuscripts in both

Chinese and Xixia writing. Most of its contents were written in Chinese, but

Xixia writing was used for terms specific to certain periods that might have

been misunderstood otherwise. I stayed indoors for three full months in order

to decipher them.

After

the valuable manuscripts’ initial discovery in the 1970s by “illiterate

peasants” who had no concept of their value, some parts of this “treasure” are

destroyed by fire. Only later do the manuscripts come into the possession of

the author:

On a

windy day laden with whirling yellow dust, many years later, Grandpa Jiu

solemnly handed the treasure that had been hidden for the past thousand years

in a Xixia cave to a man named Xue Mo.

Further

grounding the frame story in real life, the narrator names the man who gave him

the manuscripts and also describes the weather on the day it happened. The

narrator also reinforces the lost manuscript frame story, from chapter to

chapter and section to section, referencing manuscripts by name, depending on

which of them is the source for a particular chapter. Five titles recur with

some frequency: Nightmares; Crazy Ramblings of Ajia; Tale of the Goddess; True

Records of the Curses; and Historical Mirror of Forgotten Events. These

frequent citations serve to bolster the meta-fictional conceit, the story

within a story.

Adding

another layer of significance, the narrator Xue Mo describes Diamond Maiden

Cave, the grotto where the manuscripts were discovered, as “one of the totemic

guideposts of my life”: “my religious beliefs and creativity are all linked to

it.”

The

cave itself is named for a deity:

Diamond

Maiden is one of the deities of Tantric or Esoteric Buddhism. She is the main

deity among the millions and millions of Dakini goddesses. According to legend,

there are two Diamond Maiden caves in China. One of them is in the province of

Xinjiang; its exact location is no longer known. The other is in Liangzhou.

As

for the contents of the rediscovered manuscripts, the narrator describes them

as follows and details the process whereby he crafted them into the novel we

are now reading:

They

recorded events in a village named Diamond Clan, with emphasis on the spiritual

journeys of a monk, or madman, named Jasper and a woman named Snow Feather… I

spent several years interpreting, clarifying, researching, and footnoting the

seemingly confusing and antiquated language order to present them to my readers

in a style akin to a vernacular novel.

When

Xue Mo refers to the “vernacular novel,” he is talking about a traditional

Chinese novel. As discussed above, the framing device detailing the ostensible

real-life origins of the (fictional) tale is often found in traditional

fiction, and there are other ways that Curses of the Kingdom of Xixiaresembles

traditional Chinese vernacular novels. For instance, the chapters are headed by

poems or parts of poems that relate to the chapter’s content. In addition, the

novel’s structure is episodic, with lyrical passages alternating with action

sequences, all of it punctuated by dashes of humor, some of it witty and some

of it earthy. Last but not least, the novel illustrates a guiding sense of

moral principles and Buddhist concepts, including impermanence, the illusory

nature of reality, karma, samsara, and the principle of nonviolence.

The

Characters and Their Stories:

As

the narrator writes at the beginning, the novel centers on the intertwining

fates of two characters, Jasper and Snow Feather:

Jasper

is a protagonist of this book. He was thought to have been a monk who had

broken his vows. The ludicrous romance between Jasper and Snow Feather brought

fame to Toad Cave [Diamond Maiden Cave]. This book is about them.

Jasper’s

spiritual journey is the focus of many of the tales in the book. He exists in

recent memory, as people known to the narrator report having seen him in the

past. At some point he came to be known as Indigent Monk, and later as Mad

Monk. Then he disappeared. But these events are not as central to the story as

Jasper’s quest for enlightenment.

Gifted

with the extraordinary ability to see ghosts, this exceptional young man has

long wished to become a monk, an aspiration his mother supports. However,

Jasper’s quest is complicated by conflict with his father Braggart, a local

thug turned village headman. Braggart wants Jasper to marry Snow Feather and

join the “family business” of bullying the local people for fun and profit. If

the opposition of a politically powerful parent weren’t enough, Jasper’s deep

physical attraction to Snow Feather further complicates his progress towards

purity.

Snow

Feather, sometimes identified as Diamond Maiden, is a Dakini/Vajrayogini with

the ability to fly swiftly from place to place. This will ultimately get her in

trouble with the authorities when she uses her power to commit some

high-profile heists. After she steals sheep (out of necessity and compassion in

a time of famine, the authorities catch up with her and try to bring her to

justice. Their attempt to carry out her death sentence fail when a goodhearted

bullock spares her life. Sent to a labor camp, she will treat prison as “a

ritual space.” As the author comments,

“herding sheep in the desert can help one’s soul settle into clarity. If you

lie on the sand and look at the cloudless sky, you will feel the clear

brightness dissolve you, and your consciousness will resemble the void.” This reflects Xue Mo’s emphasis on the

spiritual dimension of the natural world.

Snow

Feather is portrayed as a filial daughter to her elderly and infirm mother.

Stigmatized by her fellow townsfolk for her past status as a sex worker, Snow

Feather’s mother endures persecution. Snow Feather manages to protect her for a

time, but ultimately the mother is subjected to a cruel death by the sadistic

local authorities. But she means more to the story than her victimization would

imply, for Snow Feather’s mother exemplifies the practice of nonviolence. In

one key scene, the women have fled to the mountains, seeking refuge from vengeful.

Snow Feather wants to shelter in a cave, but a family of bears is already

living there. The bears, who have cubs, are prepared to defend their territory,

and for her part Snow Feather is willing to fight them for it and kill them if

necessary. However, the mother admonishes her daughter to choose compassion and

kindness rather than violence. The women negotiate with the bears, and Snow

Feather constructs a treehouse near the cave. Thanks to the mother’s

intercession, Snow Feather and her mother coexist peacefully with the bears,

and later the bears will become their guardians.

The

third primary character is Ajia, a local deity who has been watching over

Liangzhou for a thousand years. A bit of a trickster figure, Ajia is described

as a storyteller par excellence:

Ajia’s

narratives were very good — they were much better than mine — even though I’m a

writer and the legendary Ajia was a nobody. He wasn’t even a farmer since he

had no land, no agricultural implements, and no desire to work. Back then, no

one would hire Ajia as a laborer. So he went to a wealthy household during meal

times. Its manager would say, “Come and eat!” And Ajia would eat noisily and

self-righteously. Later, Ajia became a butcher. And then because of special

karma, he became a guardian god. But that will be the subject of another book.

While

Ajia plays an important supporting role in the story of Jasper and Snow

Feather, he also plays a unique, meta-fictional role. Unlike the other

characters, he is able to move back and forth between the world of the

narrative and the world of the narrator, sometimes participating in the story

and interacting with other characters, and at other times bantering with the

narrator outside of the story per se. For example, Chapter 6, “Origin of the

Flying Thief,” is an account of events from Ajia’s point of view, which the

narrator is more or less transcribing. In one particularly vivid passage about

the feeble attempts of local police to catch Snow Feather after a spectacular

theft, the narrator reels off a string of increasingly exaggerated and

ridiculous metaphors contrasting the virtuosic thief with the inept police

(“yamen runners”):

Who

was the thief? This thief was a blue steel blade, created through forging

hundreds of times, with thousands of times of hammering each round, while the

yamen runners were just rusty iron scraps! This thief was a treasured

broadsword capable of slicing through metal as if it were mud, while the yamen

runners were but a tong [sic] used in a kitchen stove. This thief was bubbling,

boiling water, while the yamen runners were but the crystals of dried urine.

Ajia wanted to give many more metaphors, but I shouted and stopped him,

“Enough! Aren’t you just a minor guardian deity? You’re just an ant pretending

to be an animal by wearing a bridle-headstall!” Ajia sniggered, “Okay, okay! I

won’t rob your right to talk. In the future, you should stop robbing the

philosophers of their right to talk too. You be a novelist and I’ll be a

guardian god!”

The

narrator breaks away from the story into a humorous exchange between himself

and Ajia, which begins when the narrator interjects, “Ajia wanted to give many

more metaphors, but I shouted and stopped him.”

By

stepping back from the storyline, the narrator calls attention to the illusory

quality of fiction, reminding the reader not to become too immersed in a story

that is not real.

The

narrator picks up the repartee several pages later, shifting seamlessly into

metafiction:

Ghosts

couldn’t enter monasteries since there was always the guardian deity, Ajia! The

only time Ajia would allow ghosts to enter was when the monks were performing

the Mengshan Alms-Giving Ritual. That was when all ghosts — fat ones, skinny

ones, male ghosts, and female ghosts — would enter the monastery cautiously but

self-righteously. Ajia loved to watch the shy female ghosts, although he would

never admit to it. The ghosts of Liangzhou are just like the folks of

Liangzhou. Ghosts are just like people. Oh, I forgot, Ajia was a deity, not a

ghost. Please don’t take offense, Ajia! However, there’s almost no difference

between ghosts and deities. Deities are but ghosts with power. What are you

glaring at me for? You pick up a sieve and think you own the sky? If you’re

worshiped, then you are a god. But if you’re not worshiped, then out you go

with a sprinkle of vinegar! What do you think you are? Can you shit gold? Can

you pee silver? Can you make me a section chief? I suggest you take it easy. We

all know that you, Ajia, are no more than a poor ghost with power, with not

even enough cash to fill a plate!

Midway

through the paragraph, the narrator goes from referring to Ajia in the third

person to addressing him directly in the second person. Interestingly, the

reader does not have direct access to Ajia’s reactions or anything he says. We

can only guess at Ajia’s side of the conversation based on how the narrator

responds to him, an experience akin to hearing only one side of a telephone

conversation. Such exchanges between the narrator and Ajia enliven the tale

with humor, while also imparting useful information. The paragraph above is

rich in information about local folk ways and beliefs, and it also reinforces

the narrator’s portrait of Ajia as a transgressive trickster (“Ajia loved to

watch the shy female ghosts, although he would never admit to it.”).

In

addition to Snow Feather’s benevolent and long-suffering mother, positive

secondary characters includethe narrator’s guru Grandpa Jiu, Jasper’s teacher

Monk Wu, and John the Christian missionary, who pops up periodically for

meaningful philosophical conversations with the main characters. These benign

characters must often contend with a handful of antagonists, chief among them

Braggart, Jasper’s gangster-like father.

Many

of the subplots centering on Diamond Clan village feature Braggart. A reader

can infer that during the Republican period (1911 – 1949), Braggart was a hired

gun for local landlords and other powerbrokers. After 1949, he rises to “clan

head” (apparently a veiled reference to his becoming the village cadre).

Braggart is motivated by a lust for power, and he enjoys being widely feared.

His violence and cruelty know few limits. Braggart has a henchman named Kuan

San, who often does his bidding. In a karmic twist, Braggart is disabled in an

incident involving one of his children, and he is forced to live out his rather

long life as an object of public pity and scorn. In yet another twist, Kuan San

is revealed on his deathbed to have helped the people of Liangzhou by secretly

orchestrating a raid on a storehouse full of grain sequestered by Braggart,

thereby saving many people from starvation during the Great Famine of the late

1950s:

It

was said Kuan San confessed on his deathbed that he was responsible for the

“Chicken Feather Notices” that led to the grain robbery incident. He only

wanted to let the villagers eat a full meal and not starve to death, not

expecting that some ended up “eating iron pellets” [being executed]. According

to Historical Mirror of Forgotten Events, a careful tally shows that the deed

Kuan San committed was ultimately a good one; since aside from the few who

stuffed themselves to death, there were no more deaths by starvation in the

village after the Chicken Feather Notices. To exchange the lives of the few who

were shot for the ultimate survival of Diamond Clan — this was a winning trade,

the matter how one tallied it.

This

passage highlights the importance of karma in the lives of ordinary people.

Indeed, karma is a pervasive force. At one point, Ajia remarks that the reason

Snow Feather must endure so many trials and tribulations is that she broke a

promise, and there will always be a karmic consequence for transgression.

The

passage cited above also serves as an example of the novel’s nonlinear concept

of time. Within the frame of the novel, Historical Mirror of Forgotten Events

is a 1000-year-old manuscript dating from the Xixia; and yet it treats

twentieth century events as history.

Butcher

Zhang, despite a rather checkered past, is in the right place at the right time

and gains salvation. Conversely, for Cripple Big, another skilled local

artisan, there is no redemption. Although he had long been a filial son, he

ultimately lures his mother into a trap, sacrificing her to end a feud between

Diamond Clan village and their bitter rivals, Diamond King village. Cripple Big

has other people’s blood on his hands as well, those he murdered so he could

fashion their skins into ritual objects. His sins are too great for salvation.

The

passage quoted above also highlights the novel’s nonlinear concept of time.

Within the frame of the novel, Historical Mirror of Forgotten Events is a

1000-year-old manuscript dating from the Xixia; and yet it treats twentieth

century events as history. As the narrator says in an aside towards the end of

the book, neatly summing up the tale’s temporal ambiguity:

I

heard that this was a prophecy.

I

also heard that this was probably a fable.

The

collapsing of time into a simultaneity recurs throughout the novel in various

guises. For instance, the morally ambiguous character Butcher Zhang exists in

multiple historical periods. He is described as a contemporary man who steals

Monk Wu’s wok, vajra scepter, and other ritual items; “[but] in historical

records, Butcher Zhang seems to have lived during the Tang or the Xixia

dynasty.” The narrator confesses to his

temporal confusion around this character when he sketches a scene in which

Butcher midst of forging a horseshoe: “I can’t tell whether he wore a Xixia

outfit. His appearance was always vague in Jasper’s nightmares.” Alluding to the unreality of dreams, the

narrator often stresses the illusory nature of, chronological time in other

passages like this one:

Nightmares’

contents are very confusing. It is not clear whether the events transpired

during the time of the Kingdom of Xixia or the present.

This

instability extends to the village of Diamond Clan itself. The narrator

confesses that its origins are an “enigma.” What’s more, the place seems to

exist simultaneously throughout time:

Judging

from the manuscript, the dates for this Diamond Clan were also unclear. It

seemed to have existed during the Xixia period; or it could have been the

Republican period. It could also have been any of the dynasties during the last

thousand years.

I

would be remiss if I did not include the animal characters in this discussion.

As observed above, the natural world is an integral part of Xue Mo’s moral

universe. Celestial objects and natural forces that are typically regarded as

inanimate are portrayed in Curses of the Kingdom of Xixia as animate and having

agency. Scattered throughout the book are passages such as these: “the sun

shouted loudly” ; “[the] mountain wind blew vehemently” ; “[the] stars would

laugh loudly” ; and “[the] air was full of the bright laugh of sunshine.” Likewise, members of the animal kingdom are

portrayed as having personalities and moral agency. Not only is there a family

of bears who become Snow Feather and her mother’s, there are also ravens, a

horse, a benevolent bullock, and pythons that earn merit by guarding the

manuscripts. All of these creatures play positive roles in the story and often

have the ability to communicate with humans. Although most of the animals in

Curses of the Kingdom of Xixia are allies of the protagonists, there are other

animals which are their “karmic foes”— chiefly the red bats, which must be

fought off and killed in a pivotal scene.

Deities

like Snow Feather and Ajia are not the only supernatural figures in the novel’s

cast of characters. There is also a significant population of ghosts, many of

them hungry ghosts — victims of the man-made famine of the late 1950s. Snow

Feather (who, like Jasper, is also able to see any interact with ghosts), has a

frightening encounter with the ghosts of some of her relatives who attempt to

kill her and eat her. Desperate to stay alive during the famine, they turned to

cannibalism, but they died anyway. There was no one alive to bury them, and all

of the unburied dead became hungry ghosts, doomed to wander the landscape and

never find rest, forever reenacting their futile search for food.

It is

worth noting that not only is time simultaneous rather than linear, identity or

selfhood is fluid. The latter could be viewed as a corollary of the former, the

ambiguity or instability of Butcher Zhang’s historical period being a case in

point. In one passage, the narrator confesses:

I was

never able to figure out the relationship between Jasper, Ajia, and Snow

Feather of Nightmares and those in the other manuscripts. Although they have

the same names, they seem to have experienced different life trajectories.

Elsewhere,

the narrator Xue Mo mentions in passing that in a previous life he had been a

butcher and possibly a wolf. The existence of past lives and multiple,

divergent life experiences is a reflection of the Buddhist concept of samsara,

whereby the soul lives many lives. Similarly, the lack of fixed identities is a

hallmark of the notion of impermanence, and the instability of chronological

time in the novel points to the illusory nature of time and phenomena.

All

that is certain in the world of the novel are certain principles: impermanence,

illusion, and nonviolence. Xue Mo devotes an entire section near the end to an

impassioned plea for non-violence, in which he also questions received his

story of graphical categories like “heroism” and “patriotism.” He argues

forcefully that “[the] heads of the commoners are by far more important, by

far, than the owner of an Emperor.” In

the context of the mercilessly bloody Mongol conquest of the Northern Song

dynasty and the kingdom of Xixia (among others), Xue Mo offers a nontraditional

reading of history. He castigates cultural heroes like the poet Lu You (1125 –

1210 CE), who urged others to take up arms against the invading Jin forces, and

he praises the long-vilified Southern Song official Qin Kuai (1091 – 1155) as a

pacifist motivated by a desire to protect the people:

Because

of a “traitor” named Qin Kuai, the heads of the people of the Southern Song

remain safely glued to their necks.

It is

hard to overstate how shocking these assertions would be to most readers in

China. It would be seen as akin to praising Chamberlain’s appeasement policy

and condemning Churchill. However, in the case of the Mongol conquest of the

vast territory that composes contemporary China, Xue Mo suggests that the

Mongols were an unstoppable force. For the people of Xixia, resistance led to

violent death on a massive scale in the extermination of an entire population.

He points out that surrender allowed the common people to keep on living. He

makes it clear that it is the common people who are sacrificed and more,

whether on the battlefield or at home. Moreover, if one takes a long view of

history, the Mongol Yuan dynasty, like any other dynasty, could not last

forever.

Because

the frame story rests the narrative on a hodgepodge of manuscripts, this

portmanteau of a novel can accommodate such digressions. The narrator always

circles back to the three main characters.

Conclusion:

Curses

of the Kingdom of Xixia, spanning centuries, populated with numerous vivid characters

(divine, human, animal, supernatural), and threaded with philosophical and

spiritual observations, resists any simple summation. By way of conclusion, I

will quote the wise fool Ajia:

“I’m

a firefly,” Ajia coughed lightly, “although I know I can’t change the world, I

still try to give off my own light.”

Author’s

introduction:

Andrea

Lingenfelter , A poet, scholar of Chinese literature, and a widely published

translator of contemporary Chinese-language fiction (Farewell My

Concubine,Candy) and poetry by authors from Mainland China, Taiwan and Hong

Kong.

/span>